Incorect Politic

Ianuarie 7, 2020

Inca un fals document bagat sub nas publicului drept original si amplu adoptat in multiple lucrari de referinta de catre propagatorii teoriei Holocaustului.

SS Rentabilitatsberechnung, care se traduce drept „calcul al profitabilitatii “ , a fost citat pe scară largă in toata literatura favorabila Holocaustului ca o sursă care arată cât de mult profit se asteptau SS să realizeze din media muncitorului sclav.

TRADUCERE MECANICA:

În ultimii 60 de ani, un document obscur numit SS Rentabilitatsberechnung care intenționează să calculeze profitul generat de mașina de ucidere a muncii sclavilor naziste a fost citat de istorici, scriitori și rabini, expus la muzee și folosit în sălile de clasă din întreaga lume.

Problema este că pare să fie, dacă nu chiar o fabricare dreaptă, atunci cel puțin un artefact de proveniență neprovizibilă. Aceasta ar fi o problemă în orice domeniu istoric, dar este deosebit de îngrijorătoare în lumea mizelor mari ale istoriei Holocaustului, în cazul în care chiar și chestiuni de rutină de revizuire istorică furnizează furaje negatorilor Holocaustului

SS Rentabilitatsberechnung, care se traduce ca „calcul profitabilitatea“ , a fost citat pe scară largă ca o sursă care arată cât de mult profit SS de așteptat să realizeze din media muncitorului sclav. Acesta a fost în circulație de zeci de ani și până de curând a fost trimis în audio-ghidul exponatului Auschwitz, Not Long Ago, Not Far Away la The Museum of Jewish Heritage – A Living Memorial to Holocaust, din New York.

Peste 135.000 de vizitatori au participat la expoziție de la deschiderea lunii mai. Oficialii muzeului estimează că aproximativ 70% dintre vizitatori se bazează pe un program audio și video de 90 de minute pentru a-i ghida prin cele trei etaje ale artefactelor, documentelor și prezentărilor.

La începutul acestei luni, curatorii expoziției au șters în liniște o taxă uimitoare cu privire la programul de muncă forțată nazistă din ghidul audio. Ștergerea a reprezentat o singură frază de 13 secunde din ghidul de 90 de minute: „În timpul celui de-al Doilea Război Mondial, SS a calculat că, după costuri precum cremarea, dar fără a include valoarea oaselor utilizate în îngrășământ, profitul obținut din fiecare deținut avea aproximativ 745 de dolari. ” Dar referința expirată la calculul rentabilității a fost suficient de dramatică pentru a fi fost preluată și parafrazată de The New York Times în revizuirea sa din 8 mai .

Episodul oferă o lecție de precauție cu privire la modul în care un document dramatic de proveniență problematică s-a insinuat în înțelepciunea convențională despre Holocaust – și poate a furnizat, din neatenție, muniție negatorilor.

Am primit pentru prima dată o copie slabă a unei copii a documentului SS în urmă cu mai bine de 12 ani de la un supraviețuitor octogenar. El a spus că a primit-o de la văduva unui rabin care o găsise în dosarele soțului său răposat. „Este șocant, dacă nu ai fost acolo și ai văzut-o.”

Într-adevăr.

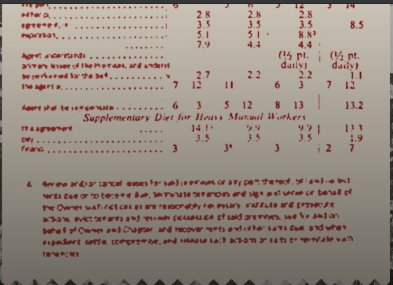

Acesta enumeră „venitul mediu zilnic de închiriere” al RM 6, prețul pe care companiile private SS l-au taxat pentru un muncitor calificat. Scăzând 70 pfenniguri pentru alimente și cheltuieli aeriene lasă un profit brut de 5,30 RM pe zi.

Această sumă se înmulțește cu 270 de zile – nouă luni – speranța medie de viață a unui lucrător forțat. Acest lucru a dus la 1.431 RM.

Adăugați un alt RM 200 din „Produse pe valoarea rațională a cadavrelor” – dinți mari, îmbrăcăminte, obiecte de valoare și bani. După deducerea RM 2 pentru cremare, dar au observat posibilele încasări din „reciclarea oaselor și a cenușii”, profitul net proiectat pentru lucrător de sclavi ajunge la 1.631 RM, aproximativ 652 USD, sau, ajustat pentru inflație, 10.568 USD în 2019. (Curatorii expoziției au folosit o rată de schimb diferită decât eu.)

Aici, pe această singură bucată de hârtie, a fost o revelație aparent demnă de naziști: valoarea vieții umane redusă la un calcul rece al profitului și costului. Tatăl meu a fost un elev al lagărelor de muncă și am vrut cu disperare să folosesc acest document îngrozitor de groaznic în cartea la care lucrez despre documente naziste.

Dar au fost probleme: fără antet, fără dată și fără semnătură, nici măcar cu o ștampilă din cauciuc. Această absență a aprovizionării m-a înrăutățit. Ultimul lucru pe care mi-l doream era să subminez din greșeală această istorie oribilă din cauza unui document suspect.

Natalia Aleksiun, profesoară de istorie modernă evreiască la școala absolvită a colegiului Touro, a declarat că denunțătorii Holocaustului au încercat să utilizeze chiar și inexactități istorice minore pentru a discredita întreaga istorie a genocidului.

În timp ce conducea propriile sale cercetări, ea se găsise pe site-uri web care „nu numai că spuneau ura, dar se angajau în descoperirea și discuțiile despre modul în care cuvintele și termenii erau traduse, discuții serioase”.

Cu ani în urmă, am intervievat Franciszek Piper, istoricul Auschwitz responsabil în mare parte pentru revizuirea descendentă a numărului de victime de la Auschwitz, de la 4 milioane la 900.000 și 1.1 milioane. După eliberarea taberei, anchetatorii Armatei Roșii au înmulțit pur și simplu capacitatea teoretică a camerelor de gaz cu numărul maxim teoretic de zile de funcționare a acestora. Piper a analizat, în schimb, jurnalele de transport și alți factori în derivarea cifrei sale inferioare, care a fost în mare parte acceptată de istorici. Piper și-a amintit cu atenție cum negatorii Holocaustului arătau cu atenție concluziile sale pentru a discredita genocidul în întregime, în ciuda protestelor sale stăruitoare, menționând că cea mai mare parte a evreiei poloneze era deja moartă în momentul în care camerele de gaz de dimensiuni industriale deveneau funcționale.

Căutând variante de „ SS Rentabilitatsberechnung”, „ Calculul rentabilității SS” sau „prizonierii SS 270 de zile”, am fost surprins să văd că apare de multe ori în multe limbi. Interesant, indiferent de limbă – engleză, germană, rusă, ebraică sau poloneză – fiecare referință a reprodus în mod fidel aceleași numere și matematică.

Cu toate acestea, fiecare citație și toți cei pe care i-am contactat au citat ceea ce s-a dovedit a fi o sursă secundară. Căutarea originalului a condus adesea la o urmă de note de subsol care citează alte cărți, dar niciodată documentul în sine. Noua lume curajoasă a copiilor și copiilor pe internet o răspândise și mai mult.

Cea mai veche referință – și cea citată de un curator al expoziției de la Auschwitz – a fost de la Eugon Kogon, un jurnalist catolic respectat și un anti-nazist străbun, care a fost închis la lagărul de concentrare de la Buchenwald timp de șase ani. Kogon este adesea credit ca primul istoric care a scris în detaliu lagărele de concentrare.

Rentabilitatsberechnung apare în 1946 cartea sa, SS Statul . Astăzi, o traducere în engleză a celei mai populare rescrieri din 1950, Teoria și practica iadului , poate fi descărcată gratuit.

„Să nu se creadă că acest calcul este propria mea lucrare”, a scris Kogon. „Provine din surse SS, și [șeful lagărului de concentrare Oswald] Pohl a ferit gelos de„ interferențe exterioare ”.”

Kogon nu oferă alte detalii sau context despre document – cine l-a scris sau când, de unde provenea sau cum a intrat în posesia sa – nimic. Curatorul muzeului Memorial Buchenwald, dr. Harry Stein, a examinat anterior arhiva lui Kogon și mi-a confirmat că nu a reușit niciodată să găsească sursa originală.

Cu toate acestea, nimic nu l-a surprins pe Robert Jan van Pelt, preeminentul expert Auschwitz și curatorul principal al expoziției Auschwitz, produs de Musealia, o companie de expoziție spaniolă, în cooperare cu Muzeul Auschwitz-Birkenau din Polonia. Muzeul Moștenirii Evreilor a extins desfășurarea expoziției până în august viitor.

„Nu am văzut niciodată altceva decât o transcriere [a calculului rentabilității]”, mi-a spus van Pelt. „ Nu l-am văzut niciodată oriunde, în nicio arhivă, sau original, sau o copie carbon, sau o fotocopie a unei copii în carbon.”

Atunci, cum a ajuns să fie atât de răspândit și să-și găsească drumul în ghidul audio al unei expoziții proeminente a muzeului din New York în 2019?

„A căzut prin fisuri”, a spus Van Pelt. Producția unui nou ghid audio pentru expoziția din New York s-a desfășurat târziu. În ultimul minut, în termenul de expirație în timp ce a fost deschisă expoziția la timp, van Pelt a spus că a fost lăsată referința la calculul dramatic al rentabilității SS. A apărut la sfârșitul opritului 54, în secțiunea „Viața în tabere”. secțiune.

„Buck se oprește cu mine”, a spus Van Pelt. „Într-un fel, este greșeala mea că a rămas.”

Tabelul de calcul nu este afișat în muzeu și nici în catalogul expoziției. Nici el, a spus van Pelt, nu a fost în catalog sau în ghidul audio multilingv de la locul precedent al expoziției de la Madrid.

Cu toate acestea, Van Pelt a avertizat să nu-l demită pe Kogon pe baza fundalului schițat al documentului de rentabilitate.

În câteva zile de la eliberarea lui Kogon în 1945, Divizia de luptă psihologică a armatei americane i-a cerut să adune un raport aprofundat privind condițiile din Buchenwald, care a devenit baza cărților sale ulterioare. Kogon a continuat să devină o figură proeminentă în viața culturală și politică a Germaniei de Vest și a primit multe onoruri și premii. A murit în 1987.

„Nu-mi vine să cred că a făcut-o cu adevărat”, a spus Van Pelt despre Kogon și despre calcul, „pentru că pur și simplu nu pare să fie omul [să facă acest lucru]”.

Cu toate acestea, Rentabilitatsberechnung nu trece testul dur al lui Van Pelt pentru legitimitate. Standardele sale au fost modelate în urmă cu 20 de ani, când istoricul britanic David Irving a dat în judecată savantul american Deborah Lipstadt și editorul ei pentru calomnie, după ce a acuzat Irving de negarea sistematică a Holocaustului.

Van Pelt a fost martorul expert al apărării pe camerele de gaz din Auschwitz. „Am avut nevoie să arăt [instanței] diligența cuvenită în tot ceea ce am citat”, a spus van Pelt. „Mai ales în ceea ce privește Holocaustul, simți că problema negării stă acolo. Sunt mai prudent decât aș fi fost acum 20 de ani, înainte să am experiență cu negările Holocaustului. ”(Irving a pierdut cazul.)

Van Pelt a recunoscut că există o tentație puternică de a folosi documentul.

„Motivul pentru care oamenii sunt atrași de acesta este acela că sugerează, într-un mod pe care niciun alt document nu îl face, că germanii pun o valoare pe o viață în valoare de nouă luni sau atât de multe zile de profit pur.”

Germanii au avut o politică conștientă de a lucra prizonierii lagărului de muncă până când au murit. Ministrul nazist al justiției a numit-o infam, „exterminare prin muncă”.

SS -ul a închiriat muncitori în industria germană între 4 și 6 RM pe zi. Mai multe documente naziste atestă acest lucru.

Un alt document nazist arată că au cheltuit doar bănuți – „pfennigs” – în mâncare și adăpost. Rațiile din lagărele de muncă au fost stabilite la 1.300 de calorii pe zi pentru cei necalificați (profesori, avocați, lucrători cu gulere albe) și 1.700 pentru cei cu abilități „utile” (mașiniști, sudori, electricieni, cizmar). Un bărbat care face muncă fizică are nevoie de aproximativ 2.500 de calorii pe zi. Organismul compensează un deficit caloric, consumându-se pentru a rămâne în viață. Această politică de înfometare a fost planificată cu atenție. Când a fost aplicat prizonierilor sovietici de război, un general german l-a numit „anihilarea mâncătorilor de prisos”.

Corpurile au fost dezbrăcate de dinți de aur și obiecte de valoare înainte de incinerare, deși van Pelt a spus că nu a găsit nicio dovadă de la nicio sursă nazistă că oasele au fost folosite pentru îngrășământ. Având în vedere natura obsesivă a naziștilor de a înregistra totul, aceasta nu este o mică gaură.

Calculul lui Kogon a obținut o legitimitate mai mare și a fost mai citat, după ce a fost inclus în Power Without Morality , un volum din 1957 format în mare parte din documente SS, editate de Reimund Schnabel. Tomul de 582 de pagini a devenit ceva de referință despre operațiunile și structura SS.

Fotocopiile documentelor naziste efective constituie cea mai mare parte a volumului. Totuși, SS Rentabilitatsberechnung este setat în tip text simplu. Alături de ea se află notația „Z 32.” În cartea Cheia prescurtărilor, „Z = Zitat” sau „Cotații”, în timp ce „D = Dokumente” sau Documente.

Aceasta însemna că Schnabel nu reproducea un document, ci reimprima o cotație.

Acest lucru nu a oprit site-urile web, istoricii și muzeele în ultimii 50 de ani de la prezentarea greșită a „Z 32” ca număr de document sau de la utilizarea calculului ca fapt istoric.

La 5 august 1960, Știrile evreiești din Detroit au raportat că delegații catolici la un congres euharistic la München au vizitat o expoziție la lagărul de concentrare Dachau din apropiere și li s-au înmânat broșuri conținând „Documentul SS Z-32”, calculul rentabilității.

Alex Pearman, arhivist la Muzeul Memorial Dachau, mi-a trimis prin e-mail că nu a putut localiza sursa documentului menționat în articolul din 1960. Pearman a atașat totuși o altă imagine de afiș a calculului – în engleză – dintr-o expoziție din 1964 la Dachau. De asemenea, acesta avea „Z 32” tipărit în partea de jos.

Din arhivele Yad Vashem, am găsit o fotografie cu un poster similar, în germană, care afișează calculul la o expoziție neidentificată. „Z 32” a apărut în partea de jos. Surprinzător, nimeni de la Yad Vashem nu mi-a putut spune sursa fotografiei, cu atât mai puțin locația exponatului. Puteți descărca o traducere a calculului într-o limbă slavă de pe site-ul Muzeului Memorial al Holocaustului din SUA. Sursa sa? Muzeul Iugoslaviei.

Adesea, utilizarea de către un istoric a calculului rentabilității SS este ascunsă de o pistă de tip cookie cu note de subsol.

În 2004, Stuart Eizenstat a descris calculul SS drept „unul dintre cele mai înfricoșătoare documente pe care le-am văzut vreodată”, în cartea sa, Imperfect Justice . El citează în detaliu documentul și aritmetica acestuia.

Eizenstat nu este intelectual ușor sau diletant. Este un fost ambasador la Uniunea Europeană, a ocupat funcția de secretar adjunct al Trezoreriei și a fost consilier principal al președintelui Jimmy Carter.

Sursa lui pentru documentul SS? O notă de subsol citată într-o carte germană despre munca sclavă nazistă. La rândul său, acea carte a notat încă o carte germană despre tratamentul nazist al inamicilor săi. Sursa acestei cărți? Puterea lui Schnabel fără morală.

În explicarea intrărilor „Zitat”, Schnabel a scris: „În fiecare caz, cotațiile indică sursa lor exactă.” Cu excepția unei „surse”, nu există decât o descriere: „Calculul rentabilității exploatării SS a prizonierilor în lagărele de concentrare .“

„Trebuie să fim extra, extra, foarte precauți tocmai pentru că trăim într-o perioadă în care fiecare mic detaliu care ar putea fi o eroare, un istoric care lipsește virgula undeva, devine o paletă politică împotriva adevărului”, a spus Aleksiun de la Colegiul Touro. „Aceasta nu este o bursă Sfântului Graal al Holocaustului, că dacă pierdem documentul pierdem adevărul.

***

Articolul în limba engleză:

How a Fake Nazi Document Fooled the Experts

A cautionary lesson in how the ‘SS Rentabilitatsberechnung,’ a dramatic document of unknown provenance, entered the conventional wisdom about the Holocaust and may have provided ammunition to deniers

HOW A FAKE NAZI DOCUMENT FOOLED THE EXPERTS

A cautionary lesson in how the ‘SS Rentabilitatsberechnung,’ a dramatic document of unknown provenance, entered the conventional wisdom about the Holocaust and may have provided ammunition to deniers

For the last 60 years, an obscure document called the SS Rentabilitatsberechnung that purports to calculate the profit generated by the Nazi’s slave labor killing machine has been quoted by historians, writers and rabbis, exhibited at museums, and used in classrooms around the world.

The problem is that it appears to be, if not an outright fabrication, then at the very least an artifact of unprovable provenance. This would be a problem in any historical field but is especially troubling in the high stakes world of Holocaust history where even routine matters of historical revision provide fodder to Holocaust deniers

The SS Rentabilitatsberechnung, which roughly translates as “profitability calculation,” has been widely cited as a source that shows how much profit the SS expected to realize from the average slave laborer. It’s been in circulation for decades and until very recently was referenced in the audio guide of the acclaimed exhibit Auschwitz, Not Long Ago, Not Far Away at The Museum of Jewish Heritage—A Living Memorial to the Holocaust, in New York.

More than 135,000 visitors have attended the exhibit since it opened last May. Museum officials estimate about 70% of the visitors rely on a 90-minute audio and video program to guide them through the exhibit’s three floors of somber artifacts, documents, and presentations.

Earlier this month the exhibit’s curators quietly deleted a stunning charge about the Nazi forced labor program from the audio guide. The deletion amounted to a single, 13-second sentence from the 90-minute guide: “During World War II, the SS calculated that, after costs such as cremation, but not including the value of bones used in fertilizer, the profit made from each prisoner was roughly $745.” But the expunged reference to the profitability calculation was dramatic enough to have been picked up and paraphrased by The New York Times in its in its May 8 review of the exhibit.

The episode provides a cautionary lesson in how a dramatic document of problematic provenance insinuated itself into the conventional wisdom about the Holocaust—and may have inadvertently provided ammunition to deniers.

I first received a poor copy of a copy of the SS document more than 12 years ago from an octogenarian survivor. He said he had gotten it from the widow of a rabbi who had found it in her late husband’s files. “It’s shocking, unless you were there and saw it.”

Indeed it is.

It lists “daily average rental income” of RM 6, the price the SS charged private companies for a skilled worker. Subtracting 70 pfennigs for food and overhead leaves a gross profit of RM 5.30 per day.

This sum is multiplied by 270 days—nine months—the average life expectancy of a forced laborer. This yielded RM 1,431.

Add another RM 200 from “Proceeds per rational value of corpses”—gold teeth, clothing, items of value, and money. After deducting RM 2 for cremation but noting possible proceeds from “bone and ash recycling,” the projected net profit per slave laborer comes to RM 1,631, about $652, or, adjusted for inflation, $10,568 in 2019 dollars. (The exhibition curators used a different rate of exchange than I had.)

Here, on this single piece of paper, was a revelation seemingly worthy of the Nazis: the value of human life reduced to a cold calculation of profit and cost. My father was an alumnus of the labor camps and I desperately wanted to use this elegantly awful document in the book I am working on about Nazi documents.

But there were problems: no letterhead, no date, and no signature, not even a rubber-stamped one. This absence of sourcing made me wary. The last thing I wanted was to inadvertently undermine this horrible history because of a suspect document.

Natalia Aleksiun, professor of modern Jewish history at the graduate school of Touro College, said Holocaust deniers have tried to leverage even minor historical inaccuracies to discredit the entire history of the genocide.

While conducting her own research, she had found herself on websites that were “not only spewing hatred but engaged in discovery and discussions of how words and terms were translated, serious discussions.”

Years earlier I had interviewed Franciszek Piper, the Auschwitz historian largely responsible for the downward revision of the number of victims at Auschwitz from 4 million to between 900,000 and 1.1 million. After the camp was liberated, Red Army investigators had simply multiplied the theoretical capacity of the gas chambers by the theoretical maximum number of days of their operation. Piper instead analyzed transport logs and other factors in deriving his lower figure, which has largely been accepted by historians. Piper ruefully recalled how Holocaust deniers gleefully pointed to his findings to discredit the genocide entirely, despite his strenuous protests noting that most of Poland’s Jewry was already dead by the time the industrial-size gas chambers became operational.

Searching variations of “SS Rentabilitatsberechnung,” “SS Profitability Calculation,” or “SS prisoners 270 days,” I was surprised to see it come up many times in many languages. Interestingly, no matter the language—English, German, Russian, Hebrew, or Polish—every reference faithfully reproduced the same numbers and math.

Yet every citation, and everyone I contacted, had quoted what turned out to be a secondary source. Searching for the original often led to a trail of footnotes citing other books but never the document itself. The brave new world of internet copy-and-paste had spread it around even more.

The earliest reference—and the one cited by a curator of the Auschwitz exhibition—was from Eugon Kogon, a respected Catholic journalist and an outspoken anti-Nazi who was imprisoned at the Buchenwald concentration camp for six years. Kogon is often credited as the first historian to write of the concentration camps in detail.

The Rentabilitatsberechnung appears in his 1946 book, The SS State. Today, an English translation of the more popular 1950 rewrite, The Theory and Practice of Hell, can be downloaded for free.

“Let it not be thought that this calculation is my own handiwork,” Kogon wrote. “It comes from SS sources, and [concentration camp head Oswald] Pohl jealously guarded against ‘outside interference.’”

Kogon provides no further details or context about the document—who wrote it or when, where it came from, or how it had come into his possession—nothing. The curator of the Buchenwald Memorial museum, Dr. Harry Stein, had previously reviewed Kogon’s archive and confirmed to me that he has never been able to find the original source.

Yet, none of this surprised Robert Jan van Pelt, the preeminent Auschwitz expert and lead curator of the Auschwitz exhibition, which was produced by Musealia, a Spanish exhibition company, in cooperation with the Auschwitz-Birkenau Museum in Poland. The Museum of Jewish Heritage has extended the exhibit’s run to next August.

“I’ve never seen anything but a transcript [of the profitability calculation],” van Pelt told me. “Never seen it anywhere, in any archive, or original, or carbon copy, or photocopy of a carbon copy.”

How, then, did it get to be so widely disseminated and find its way into the audio guide of a prominent New York museum exhibit in 2019?

“It fell through the cracks,” van Pelt said. Production of a new audio guide for the New York exhibit was running late. In the last-minute, hurly-burly deadline of getting the exhibit opened on time, van Pelt said the reference to the dramatic SS profitability calculation was left in. It appeared at the end of Stop 54, under the “Life in the Camps” section.

“The buck stops with me,” van Pelt said. “In some way, it’s my mistake that it stayed in.”

The calculation table is not on display in the museum nor is it in the exhibition’s catalog. Nor, van Pelt said, was it in the catalog or multilingual audio guide at the exhibit’s prior venue in Madrid.

Still, van Pelt cautioned against dismissing Kogon entirely based on the sketchy background of the profitability document.

Within days of Kogon’s liberation in 1945, the U.S. military’s Psychological Warfare Division asked him to assemble an in-depth report on conditions in Buchenwald, which became the basis of his later books. Kogon went on to become a prominent figure in West Germany’s cultural and political life and received many honors and awards. He died in 1987.

“I can’t believe he really made it up,” van Pelt said of Kogon and the calculation, “because he just doesn’t seem to be the man [to do so].”

Nevertheless, the Rentabilitatsberechnung doesn’t pass van Pelt’s sniff test for legitimacy. His own standards were molded 20 years ago, when British historian David Irving sued American scholar Deborah Lipstadt and her publisher for libel after she accused Irving of systematic Holocaust denial.

Van Pelt was the defense expert witness on the Auschwitz gas chambers. “I needed to show [the court] due diligence in everything I quoted,” van Pelt said. “Especially where it relates to the Holocaust, you feel the problem of denial is sitting there. I am more cautious than I would have been 20 years ago, before I had experience with Holocaust denials.” (Irving lost the case.)

Van Pelt admitted there was a strong temptation to use the document.

“The reason people are attracted to it is because it suggests, in a way that no other document does, that the Germans put a value on a life worth nine months or so many days of pure profit.”

The Germans did have a conscious policy of working labor camp prisoners until they dropped dead. The Nazi justice minister infamously called it “extermination through work.”

The SS did rent out workers to German industry for between RM 4 and 6 a day. Multiple Nazi documents attest to this.

Another Nazi document shows they did spend mere pennies—“pfennigs”—on food and shelter. Rations in labor camps were set at 1,300 calories a day for the unskilled (teachers, lawyers, white collar workers) and 1,700 for those with “useful” skills (machinists, welders, electricians, shoemakers). A man doing physical work needs about 2,500 calories a day. The body makes up for a caloric deficit by eating itself to stay alive. This policy of starvation was carefully planned. When applied to Soviet prisoners of war, one German general referred to it as the “annihilation of superfluous eaters.”

Bodies were stripped of gold teeth and valuables before incineration, though van Pelt said he had found no evidence from any Nazi source that bones were used for fertilizer. Given the obsessive nature of the Nazis to record everything, this is no small hole.

Kogon’s calculation attained greater legitimacy, and became more widely quoted, after it was included in Power Without Morality, a 1957 volume largely consisting of SS documents, edited by Reimund Schnabel. The 582-page tome has become something of a go-to reference about the operations and structure of the SS.

Photocopies of actual Nazi documents make up most of the volume. The SS Rentabilitatsberechnung, however, is set in plain text type. Next to it is the notation, “Z 32.” In the book’s Key to Abbreviations, “Z = Zitat” or “Quotations,” while “D = Dokumente” or Documents.

This meant Schnabel was not reproducing a document but reprinting a quotation.

That hasn’t stopped websites, historians, and museums over the last 50 years from misrepresenting “Z 32” as a document number or using the calculation as historical fact.

On Aug. 5, 1960, the Detroit Jewish News reported that Catholic delegates to a Eucharistic congress in Munich had visited an exhibition at the nearby Dachau concentration camp and were handed brochures containing “SS Document Z-32,” the profitability calculation.

Alex Pearman, an archivist at the Dachau Memorial museum, emailed me that he was unable to locate the source of the document mentioned in the 1960 article. Pearman, however, attached another poster image of the calculation—in English—from a 1964 exhibit at Dachau. It, too, had “Z 32” printed at the bottom.

From the Yad Vashem archives, I found a photo of a similar poster, in German, displaying the calculation at an unidentified exhibit. “Z 32” appeared at the bottom. Surprisingly, no one at Yad Vashem could tell me the source of the photo, much less the location of the exhibit. You can download a translation of the calculation in a Slavic language from the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum’s website. Its source? The Museum of Yugoslavia.

Often a historian’s use of the SS profitability calculation is obscured by a cookie crumb trail of footnotes.

In 2004, Stuart Eizenstat described the SS calculation as, “one of the most chilling documents I have ever seen,” in his book, Imperfect Justice. He quotes the document and its arithmetic in detail.

Eizenstat is no intellectual lightweight or dilettante. He’s a former ambassador to the European Union, served as a deputy treasury secretary, and was a senior adviser to President Jimmy Carter.

His source for the SS document? A footnote cited in a German book about Nazi slave labor. That book, in turn, footnoted yet another German book about Nazi treatment of its enemies. This book’s source? Schnabel’s Power Without Morality.

In explaining the “Zitat” entries, Schnabel wrote, “In each case, the quotations indicate their accurate source.” Except there is no “source,” only a description: “Profitability calculation of the SS Exploitation of the prisoners in the concentration camps.”

“We need to be extra, extra, extra cautious precisely because we live in a time when every little detail that might be a misquotation, a historian missing a comma somewhere, becomes a political paddle against the truth,” said Aleksiun of Touro College. “This is not some Holy Grail of Holocaust scholarship that if we lose the document we lose the truth.

***

Sursa: Tabletmag

Incorect Politic O Publicație Dizidentă

Incorect Politic O Publicație Dizidentă

One comment

Pingback: Document Fals folosit pentru a rescrie istoria